In November 1940 the Jervis Bay was the sole

escort for Convoy HX84 of thirty-seven freighters and tankers moving from Halifax to

Britain. See the

Order of Battle here.

Earlier, the German "pocket battleship"

Admiral

Scheer had slipped quietly into the Atlantic. She located the Jervis

Bay's convoy and decided to attack immediately, as it was late afternoon

and it would be difficult to find targets in the dark. Captain Fegen of the

Jervis Bay decided to advance to meet the raider, in the hope of

delaying the Germans long enough to enable most of the convoy to escape. The

convoy was ordered to scatter and the Jervis Bay, dropping smoke floats

as she went, endeavoured to bring the Admiral Scheer within the range of

her guns. |

|

|

|

In this latter aim she never succeeded. Although

her guns

fired often, every shot fell short of the enemy. A seaman who watched the

outmatched merchantman throw everything but its boiler plates at the Admiral

Scheer said it was like a bulldog attacking a bear. Meanwhile

11-inch shells

from the raider began to hit. The crew had little protection from blast or

from splinters, and casualties were heavy.

|

|

The bridge was soon hit, and with it the Jervis Bay's gunnery control

centre. Captain Fegen lost an arm and soon afterwards was killed by another

shell. Most of the officers were killed.

Nevertheless, this one-sided battle lasted

for twenty-four minutes. At the end of that period the Jervis Bay

was ablaze and her guns out of action, and the order was given to

abandon ship.

Excerpt from

Fighting

Ships Of World War 2 |

As told by Trevor Skeggs. nephew of Len Baker (AB, RNVR), Killed in Action...

The position of the convoy

was known to the Germans.

In

his book,

The position of the convoy

was known to the Germans.

In

his book, Kapitän Theodore

Krancke certainly makes no secret of expecting to find convoy HX84.

("That was the convoy all right").

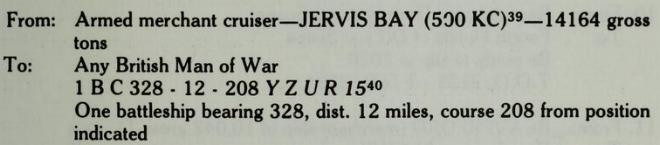

As the Jervis Bay repeatedly signalled the challenge "A",

the signals officer of the Scheer was commanded to attempt a bluff.

" ... 'She'll give her recognition signal in a moment,' said

Krancke. 'Whatever it

turns out to be repeat it at once as though we were calling her.'

Krancke was anxious to leave the enemy in doubt as to his real identity for as

long as possible in order to get close up to the convoy before opening fire. At

the moment the distance between the Scheer and the British auxiliary

cruiser was still about fifteen miles.

The auxiliary cruiser's 'A' was now followed by 'M' - 'A' - 'G' in quick

succession. The Signals Officer of the Scheer immediately had the

'M.A.G' signal repeated, but the bluff failed. The Captain of the British

auxiliary cruiser was not deceived. In any case, he probably knew quite

definitely that no friendly warship could possibly be in that quarter, and now

sheafs of red rockets began to hiss up from his decks - clearly the

pre-arranged signal for the convoy to scatter. At the same time the auxiliary

cruiser and most of the other ships in the convoy began to lay down a smoke

screen.

The distance between

the two ships was considerably less now and when it was about ten miles the

Scheer, which up to then had been racing straight towards the convoy,

turned to port to bring her broadside to bear. The guns were trained on their

targets now - the

big guns had

been ordered to concentrate on the British auxiliary cruiser while the

medium artillery was to

take a tanker not far away from her as its target.

The distance between

the two ships was considerably less now and when it was about ten miles the

Scheer, which up to then had been racing straight towards the convoy,

turned to port to bring her broadside to bear. The guns were trained on their

targets now - the

big guns had

been ordered to concentrate on the British auxiliary cruiser while the

medium artillery was to

take a tanker not far away from her as its target.

The British auxiliary cruiser, which was ahead of the second line of the

convoy, had stopped signalling, and by this time the ships were close enough

for the British Captain to have realised what he was faced with, for the

outlines of the Scheer were now clearly visible against the evening sky

and he could plainly see the guns of her triple turrets trained on him. As

unlikely as it might seem, he had encountered a German pocket battleship in

mid-Atlantic.

His

immediate reaction to this knowledge was to put his own ship between the

Scheer and what was obviously a two-funnelled passenger vessel and

probably the most valuable ship in the convoy. It floated far higher in the

water than the other vessels. The Scheer was now less than ten miles

from the nearest ship of the convoy, which was the auxiliary cruiser, and

Krancke ordered his guns to open up. A preliminary salvo screamed off from one

of the turrets to check the range. That was at 16:42 hours. ..."

His

immediate reaction to this knowledge was to put his own ship between the

Scheer and what was obviously a two-funnelled passenger vessel and

probably the most valuable ship in the convoy. It floated far higher in the

water than the other vessels. The Scheer was now less than ten miles

from the nearest ship of the convoy, which was the auxiliary cruiser, and

Krancke ordered his guns to open up. A preliminary salvo screamed off from one

of the turrets to check the range. That was at 16:42 hours. ..."

As is recognised in the muddle of battle, accounts differ. All agree on the

accuracy of the German gunnery. Survivor

Sam Patience had joined HMCS Lincoln as

quartermaster for her Canadian sea trials. He was not impressed, and jumped at

the chance to steer an ocean liner by swapping ships with a quartermaster he'd

met in Halifax who needed to get home in a hurry; the Jervis Bay had to

wait for a convoy.

Sam was

midway through the first dogwatch on his eighth day at the wheel, when the

unknown ship was spotted at 16:55 on Nov. 5th. (Guy Fawke's day). They had been

anticipating submarines below

Sam was

midway through the first dogwatch on his eighth day at the wheel, when the

unknown ship was spotted at 16:55 on Nov. 5th. (Guy Fawke's day). They had been

anticipating submarines below or

Condors

above

. "The chief

yeoman signalled with the Aldis lamp to the unknown warship. There was no

reply. The crew looked through the eyesights of the guns. They could see the

silhouette plainly. Someone suggested it was an *R-class, friendly

battleship, but Patience explained that it couldn't be because they had a

distinctive 'tiddly-top' on the funnel. They were still speculating when the

first salvo whistled over their heads and exploded in the sea about 100 yards

away. " . . . . . . . . .

"Patience handed the wheel to another sailor and went to man the

forward port gun. The crew were told to throw smoke floats over the side - big

containers like dustbins" . . . . . . "Then the Jervis Bay

steamed to port, away from the smoke and straight towards the Admiral

Scheer. The second salvo fell short, but shrapnel from an exploding shell

decapitated the man standing next to Patience." ..... "The third

salvo caught the Jervis Bay amidships, smashing the wireless office and

much of the deck superstructure. Captain Fegen ordered full speed ahead, and

steered straight towards the enemy. More explosions rocked the liner. Patience

looked up to see the bridge alight and the captain with one arm partly severed.

There were fires everywhere now. Men were on fire, too. Screaming, they jumped

over the side.

The next salvo blew the gun opposite Patience right off the forecastle,

along with its mounting and its crew. The shells arrived at a horrific

velocity. The ship bucked and rolled under the impact. The next one had to kill

him, Patience thought. Instead, its blast blew him off the gun platform and

down the well deck, dazed but only slightly injured".

All subsequent Allied accounts seem to follow the above version: from "The

Lonely Sea" :

"Two ranging salvos fell one on either side of the armed merchant cruiser,

displaying testimony to the German reputation for gunnery of a quite phenomenal

accuracy : the third salvo crashed solidly into the hull. In one stroke the

foremast was shot away, the director and range.finder wrecked, the transmitting

station, which controlled the guns, knocked out of action and the guns

themselves rendered useless for all but primitive hand control - the cables

feeding in the electrical supplies had been completely severed. The battle had

not yet properly begun, but already the Jervis Bay was finished as a fighting

unit.

Kapitän Theodore Krancke of the Admiral Scheer knew that he had

nothing more to fear from the big merchantman. He at once altered course to

overtake the fleeing convoy, only to find that his way was barred once more:

the Jervis Bay, too, had put over her helm, and was closing rapidly on a head-

on collision course." However, the German account does not exploit this

account for propaganda purposes: "Coloured rockets were still shooting

into the air from the deck of the British auxiliary cruiser. They were

different signals. Who were they intented for ? Were they still for the

scattering ships or were they perhaps warning signals to cruiser protection on

the starboard side of the convoy and therefore invisible to the Scheer ?

After a period of

twenty-three seconds, which seemed much longer, the first salvo from the

Scheer fell into the shimmering grey-blue sea, sending up vast fountains

of foamy white water sharply outlined in black at the edges. The shells

exploded between the Scheer and her target, blotting the British cruiser

temporarily from view. That first salvo had not been more than about 200 yards

from its target. A second, corrected salvo now followed from both turrets and

almost simultaneously there were flashes of gunfire from the enemy, but the

spurts of flame visible amidships and aft were small and feeble compared with

the tremendous stabs of flame and the shattering explosions from the guns of

the Scheer. They looked little more than signals, but they showed that

the enemy was returning the fire to the best of his ability and the fact that

the response was so prompt indicated that the British auxiliary cruiser had

been ready for action and that her guns were served by trained naval men. But

the return fire fell much too short, with the exception of a single shell that

fell close enough to send spray onto the deck of the Scheer, and it was

clear either that the British auxiliary cruiser had only one gun with range

enough to get anywher near the Scheer or that she had no central fire

control and in consequence her guns were firing independently." .

According to the German account, it was the fifth salvo that first

devastatingly hit the Jervis Bay.

According to the German account, it was the fifth salvo that first

devastatingly hit the Jervis Bay.

Contrary to British propaganda, we weren't the only ones with radar.

Kapitän Krancke reveals that the Admiral Scheer was equipped with

radar so secret that only a few of the crew knew about it. The accuracy of the

gunnery is thus explained.